Puhi Ariki

Collection of the artist.

The opening exhibition for the Wairau Māori Art Gallery presents a strong and very Northland-centric opening message and statement. It presents an inter-generational exhibition starting with some of the iconic first-generation contemporary Māori artists alongside some of our established and recent Māori art stars to speak powerfully to the importance of Te Tai Tokerau and Ngā Puhi artists to the legacy of Māori art.

To this idea the notion of a waka moving Māori arts and artists forward is the symbolic reference explored in the opening show. With the waterway adjacent to the Gallery outside and the cultural importance to site taken into consideration the title of the opening exhibition plays on these ideas of navigation and plotting future pathways.

The title of the opening exhibition is Puhi Ariki which pays tribute to the importance of the plumes that adorn sailing waka where puhi-maroke (the dry plume) sits above the puhi-mākū (the wet plume) at the tauihu (bow) of the waka. At the rear found atop of the taurapa (stern post) can be found the plume named puhi-ariki. It is said the that when the waka moves through the water with ease and in unison the puhi-ariki plumage shall glide along the water. Puhi Ariki is offered as a metaphor about balance, order, prosperity, and growth. This waka (being the Wairau Māori Art Gallery) is navigating future aspirations for Māori art, artists, and its place within the region and indeed for Ngā Puhi arts development within that vision and aspiration.

Puhi Ariki: Adorning the waka

Harbours, waterways and the great moana are the highways and byways of our seafaring ancestors. Māori navigated these spaces much as they do all their relationships in life - with a sense of enthusiasm, curiosity and attention. The waters of Whangārei carry a rich waka history as numerous tribal waka traditions trace relationship to this unique region. In every instance waka play a pivotal role in that journey and in the learnings that experience provides.

This opening exhibition, Puhi Ariki reflects upon the symbolic significance of waka as a way to celebrate Māori art and the aspirations of the Wairau Māori Art Gallery. Its title references the plumes that adorn sailing waka where puhi-maroke (the dry plume) sits above the puhi-mākū (the wet plume) at the tauihu (bow) of the waka. At the rear, atop the taurapa (stern post) can be found the plume named puhi-ariki. It is said that when the waka moves through the water, with ease and in unison, the puhi-ariki plumage will also glide effortlessly along the water. Puhi Ariki is offered as a metaphor about balance, order, prosperity, and growth. The waka that is the Wairau Māori Art Gallery, is invested in a future for Māori art that is ambitious and empowers Māori to lead the way for artists and for curators. It is also invested in supporting the development of Māori art within the region. With the Hatea river adjacent to the Wairau Māori Art Gallery we acknowledge the cultural history of this site. Indeed, this exhibition navigates and plots a pathway and a vision for greater visibility of Māori art. In doing so, it also acknowledges Te Parawhau ki Tai as kaitiaki o te mana o te whenua and kaitiaki and of its stories.

Puhi Ariki is told through the work of nine Māori artists spanning seven generations, and all share a whakapapa connection to Te Taitokerau – to Northland. The work of Ralph Hōtere, Selwyn Muru, Maureen Lander, John Miller, Emily Karaka, Te Hemo Ata Henare, Israel Tangaroa Birch, Nova Paul and Leilani Kake are presented here as an offering; as plumage that adorns the new waka that is this gallery space.

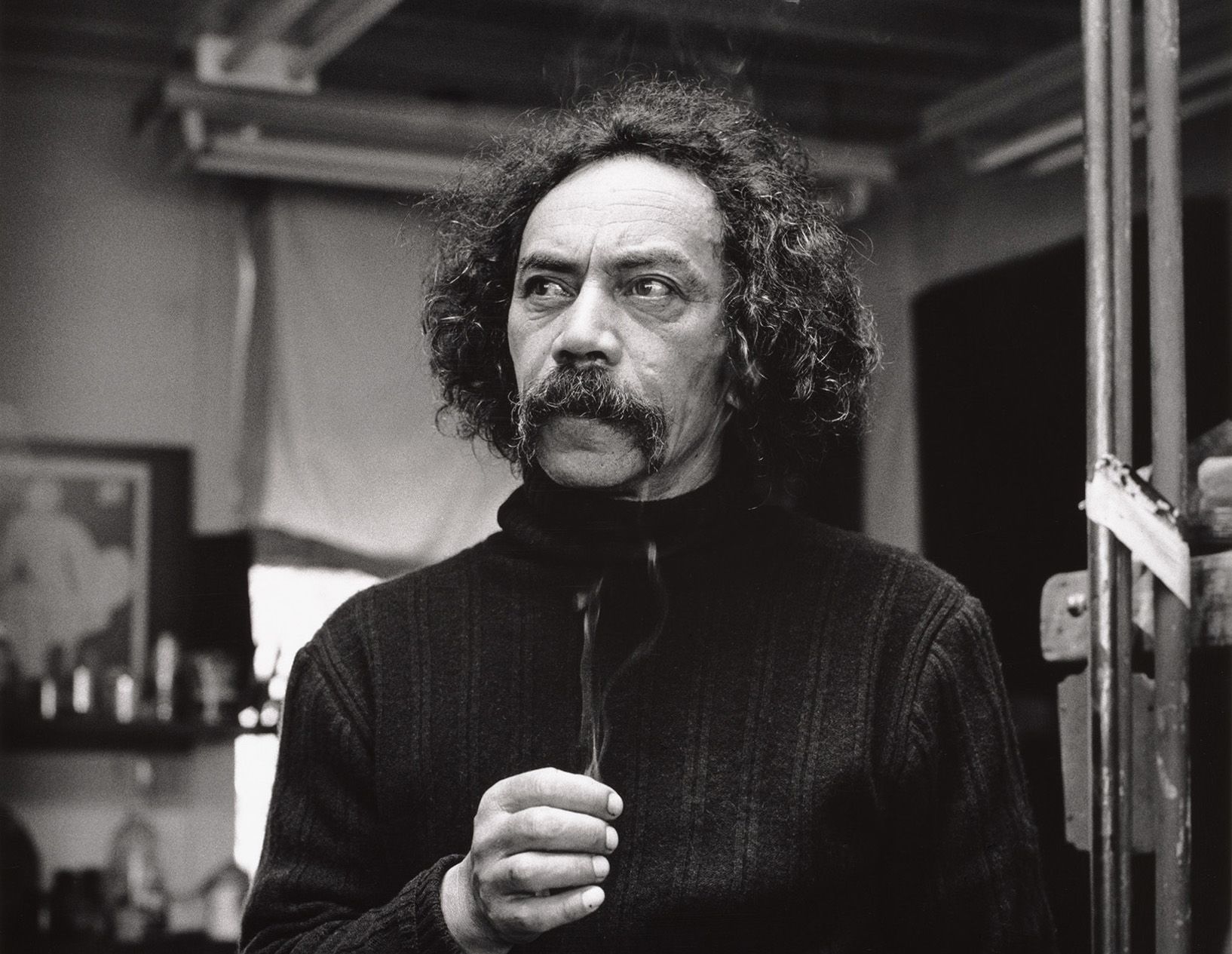

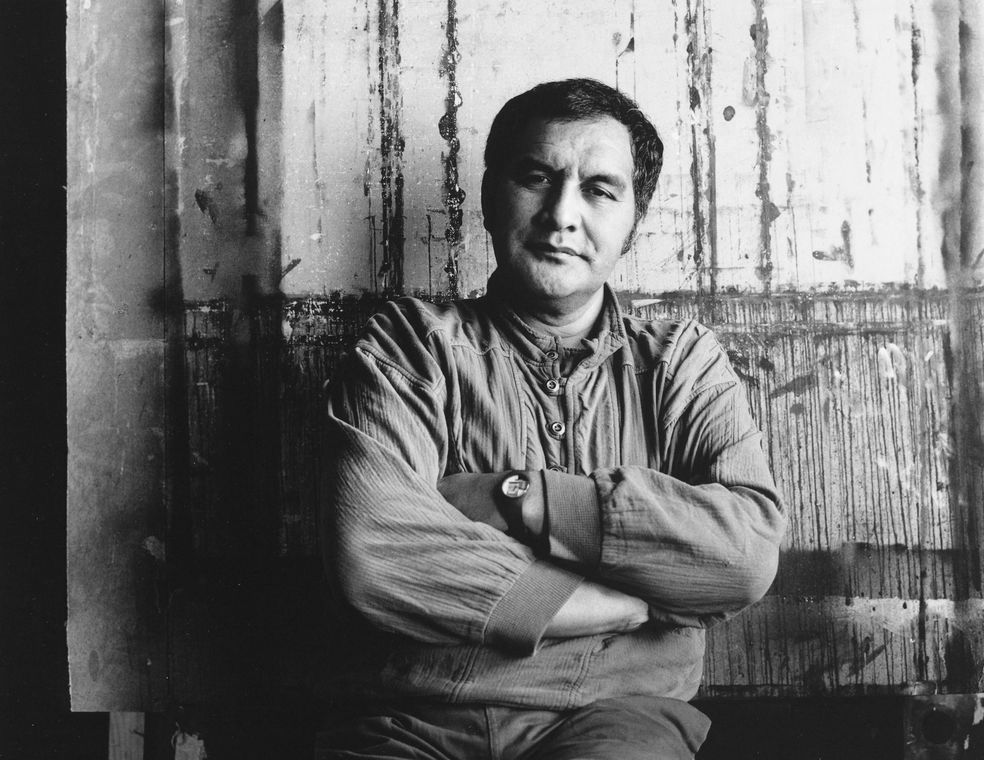

Green Painting (Zero Series), 1966-67 and Orange Painting (Zero Series), 1966-67 by Ralph Hotere (Te Aupōuri, Te Rarawa) represents the artist at a fascinating turning point in his painting practice. The subtle, yet bold abstract nature of his green and orange colour fields reflect the vast-open nature of space; much like that of the boundless moana (ocean). Interestingly, in customary Māori art, the open spaces found within the body of weaving and painting were often called the ‘moana’ as an expression of the wide-open spaces they represent. Hotere’s paintings ponder space in a similar way. His two-toned square forms that sit in the canvas, subtly introduce themselves to the viewer. They allow you to explore the dimensions of what you might interpret that space to be while also locating you in that process. Selwyn Muru (Te Aupōuri, Ngāti Kurī) is represented by two paintings from early in his career. They are tactile and energetic works that carry a sense of playful freedom that is both gestural and representational. We see this in the joyful painting Full Moon, 1963 where the moon slips under a rolling landscape with poetic ease. This vibrant energy is also evident in Untitled, c 1960 a rare explorative collage work on card. Maureen Lander (Ngāpuhi, Te Hikutū, Te Roroa) offers the elegant weaving installation Ko Puhi Moana Ariki te Tupuna, 2010. Incorporating harakeke and muka fibre, the installation cascades down the gallery wall on to the floor. Comprised of five woven cross motifs the work literally recalls the five generations of descent that connect the artist to the eponymous ancestor Puhi Moana Ariki. As intricate as the lines of genealogy themselves, Lander’s woven lines of muka thread bind concepts of DNA, whakapapa and mana Māori as a declaration and an assertion of place.

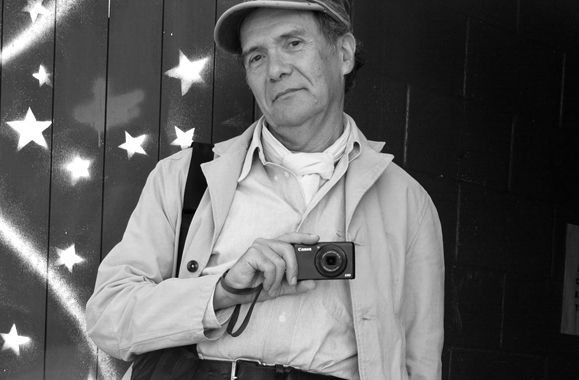

Pioneering documentary photographer John Miller nō (Ngāpuhi, Ngāi–te-wake-ki-Uta) has a practice that spans more than sixty years. His images have become iconic in the way they represent and signify the cultural and social events of Aotearoa New Zealand in the modern era. Miller presents a selection of photographs from his extensive personal archive that capture the launch of Ngātokimatawhaorua waka at The Waitangi Treaty grounds on Waitangi Day 1974. This was also the year the waka was recommissioned as a sea-going vessel by Hector Busby, Niki Conrad, Alan Karena and others, after having been an inactive museum piece at the Treaty Grounds for over thirty years. Miller’s images offer a revealing glimpse into those times and the way in which Māori navigated this most contested day in our growing history as a nation. Miller’s images endure as important cultural makers in and of themselves. This is especially so as cultural leaders pass and descendants look to reconnect themselves and their families with the people and histories captured in his photographic work.

Emily Karaka (Waikato, Ngāpuhi, Ngāi Tai ki Tāmaki, Te Kawerau ā Maki, Ngāti Tamaoho, Te Ākitai Waiōhua, Te Ahi Waru, Ngāti Mahuta, Ngāti Tahinga, Ngāti Hine) offers a new painting with PEPEHA, 2021. Here Karaka is recalling her whakapapa to the Ngāpuhi and Ngāti Hine. This vibrant painting pays tribute to her ancestor in chieftainess Riperata Maumau, who was present at the 1835 meeting of chiefs who formed the Confederation of United Tribes and drew up ‘He Whakaputanga o te Rangatiratanga o Nu Tirene’ - the Declaration of Independence of the United Tribes of New Zealand. The reciting of pepeha is a form of claims-making as they recall one’s connection to land, to people and to place. The painting depicts three flag poles that present various Māori statements of self-determination. The artist notes, “I use them to indicate the urgency and emergency faced by Ngāpuhi and Te Rarawa with respect to the settling of Treaty of Waitangi claims with the Crown. The turbulent waves refer to the troubled waters generated by the Whānau Ora Commissioning Agency and other Māori groups having to petition the courts and the Waitangi Tribunal to try to safeguard whānau, hapū, and iwi during the pandemic… …PEPEHA is thus a tapestry of events and people through time”. We also see the distinct feature of the taurapa or sternpost of a waka with the puhi ariki plumage tailing off its side, which can be interpreted as a statement of Māori emancipation and control of Māori affairs. Equally elegant and captivating is the weaving installation by master weaver Te Hemo Ata Henare (Ngāti Kahu, Ngāti Hine, Te Whakatōhea). Suspended from the gallery ceiling and floating down onto a fine woven whāriki mat on the gallery floor, this installation pays tribute to symbolism of puhi ariki as iteration of mana Māori and the importance of enduring Māori knowledge as found in the practice of raranga (weaving). Raranga has informed the artist’s own understanding of mana Māori and a Māori world view, and this is visible in the intricacies of weaving pattern, technique and sheer materiality of preparing mahi raranga. It is reiterated here as a form of knowledge that is timeless and enduring.

This is not Dying 2010 is an experimental film work by Nova Paul (Ngāpuhi, Te Uriroroi, Te Parawhau, Te Māhurehure ki Whatitiri) that the artist describes as “a love song to her whānau”. Filmed on the artist’s home marae in Porotī, Northland it documents whānau members as they go about everyday life and activity on the marae. From setting tables in the dining hall for a family gathering, to moments in the shed fixing bike parts, to swimming at the local river, This is not Dying 2010 typifies the activities of marae life that make memorable moments and enduring impressions. But it also states (as the title describes) a practice and way of cultural life that colonisation has failed to extinguish. It is accompanied by a nostalgic soundtrack offered by renowned Māori musician Ben Tawhiti on slide and steel guitar as he plays a 20-minute rendition of Whakarongo Mai - a song well known to Ngāpuhi descendants as their ‘anthem’ which adds to the work’s filmic and melancholic qualities.

Moving image and digital media artist Leilani Kake (Ngāpuhi, Tainui-Waikato, Rakahanga-Manihiki (Cook Islands) presents two related bodies of work that investigate Māori relationships and rights to land and to sacred waterways. The digital prints Swallow Green, Swallow Red, 2017 are a confronting commentary on the systemic effects of colonisation. For the artist the depiction of the mouth and moko kauae represents a Māori voice in reclaiming and re-telling New Zealand’s colonial history from a Māori viewpoint to new audiences. It challenges the legitimacy of this colonial history and suggests that it is a purposeful deception; a history that is the ‘prescribed medicine’ of the coloniser and remains a bitter pill to swallow. Wai Rua, 2022 extends this thinking in a call-to-action on the issue of our polluted waterways. Kake reflects on childhood Summers visiting Pehiāweri Marae and hot days swimming at the Ōtuihau waterfalls which is are connected to the Hatea river. Recently the Falls have experienced challenging times in terms of water health. A spike in 2018 made it unsafe for swimming and this continues to the present day. The artist maintains that when our environment is sick then we are also unwell. If the eco-system is in jeopardy, then so are the people. Wai Rua, 2022 pays tribute to the relationship we share with Papatuānuku as the personification of the land, and with its health and well-being as a living entity.

Israel Tangaroa Birch (Ngāpuhi, Ngāi Tawake, Ngāti Kahungunu, and Ngāti Rākaipaaka) offers two works that showcase his signature style of coloured and lacquered etching into a stainless-steel two-dimensional plane. They create multi-layered readings that evoke spatial dimensions both figuratively and literally in the work. Over the past year Birch has been exploring the importance of water to Māori as a statement of sovereignty but also as a moment of tidal change, both for Māori and for Māori art. Taitoko, 2022 explores Ngā Puhi narratives relating to the high spring tide, a moment of change in our waters and in our environment. The highest tides, called spring tides, are formed when the earth, sun and moon are aligned. This happens every two weeks during a new moon or full moon. High spring tide can be seen as a metaphor for a moment of tidal change in contemporary Māori art. For the artist, this tidal shift is also a nod to the Wairau Māori Art Gallery and shift taking place in the current momentum in the world of Māori art. The works’ powerful concentric spheres pulsate with a mauri - a life force that is rhythmic and alive, and much like the ocean it is the embodiment of Tangaroa – god of the sea. Ko te Mauri o Ngā Puhi he mea huna ki te wai, 2022 is also a statement about water. The work is emblazoned with the emblem of the Tino Rangatiratanga flag. Here Birch has had collaborative conversations with fellow artist Linda Munn (Ngāpuhi, Ngāi Te Rangi, Ngā Pōtiki, Te Āti Awa, Ngāi Tahu) one of the flag’s designers and the only one still living, to align the aspirations of sovereignty and self-determination also found in political conversations around water and its importance to Māori. For the artist the mauri of Ngāpuhi is hidden and embedded in the water and the Tino Rangatiratanga flag is part of that narrative and vision.

The nine artists in Puhi Ariki represent some of the ways in which Māori art continues to navigate towards new horizons with the same sense of enthusiasm, curiosity and attention that our forebears applied to their waka journeys across the great moana. They remind us that ancestral knowledge is enduring, and that the wisdom of those teachings carries today’s waka forward. The Puhi Ariki that adorn these artists’ journeys are adornments in which we can all take pride, while for the Wairau Māori Art Gallery this inaugural exhibition represents the launching of their waka. It is a milestone moment to celebrate as the tide changes and an exciting new journey begins. May this Puhi Ariki continue to navigate the shifting tides and glide across the waters to come.

Nigel Borell