Ringatoi Artist

Hutchinson works in multiple visual media, producing performance, installation, digital works, prints and sculpture as well as her signature paper cut-outs. Exhibiting internationally as well as throughout New Zealand, Hutchinson’s solo and group shows include ‘Pasifika Style’s, University of Cambridge Museum, United Kingdom (2006-8); ‘L’Art Urbain du Pacifique’, Castle of Saint-Aurent, Limousin, France (2005); ‘Samoa Contemporary’, Pātaka, Porirua (2008) and ‘This Show Is What I Do’, Institute of Modern Art, Brisbane (2005). In 2012 Hutchinson was invited to take part in ‘HOME AKL’ at Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tamaki, a major exhibition showcasing the work of significant Pasifika artists (Jul-Oct 2012). Hutchinson's works are held in the permanent collections of Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tamaki, Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetu, National Gallery of Australia, Queensland Art Gallery, The Dowse Art Museum, and the New Zealand High Commission in Washington, amongst others.

Read more

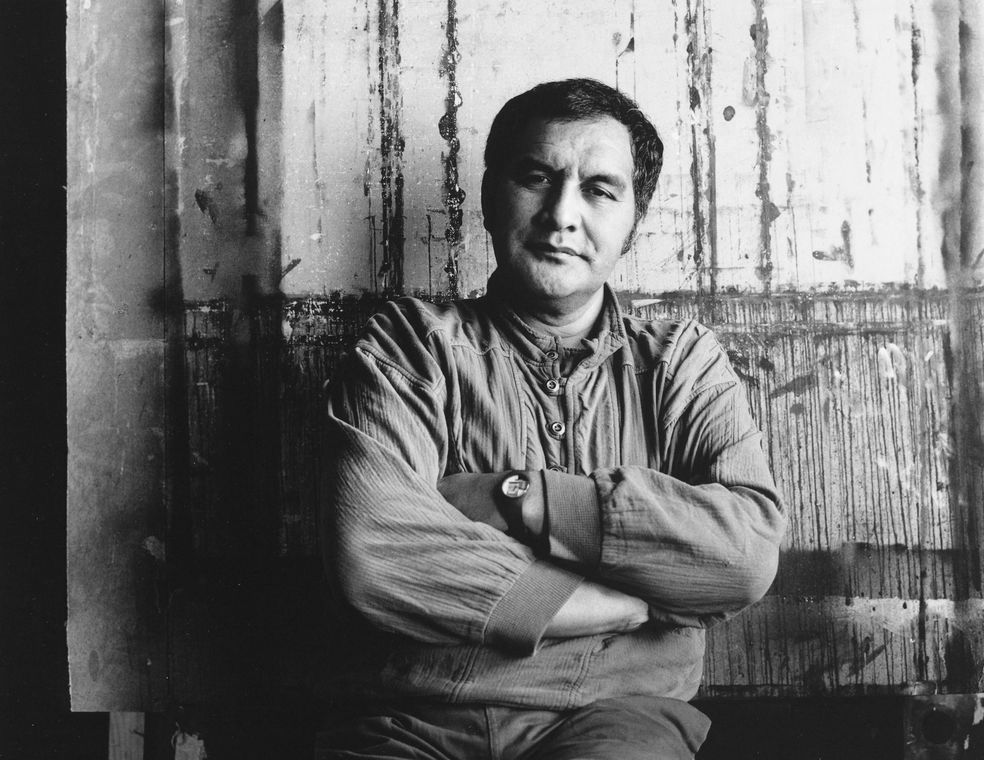

Cotton is one of New Zealand’s most celebrated artists. He completed a Bachelor of Fine Arts at the University of Canterbury’s Ilam School of Fine Arts in 1988 and in 1993, Cotton joined Robert Jahnke as a lecturer to the Toioho ki Āpiti Bachelor of Māori Visual Arts programme, Massey University, Palmerston North. That same year his paintings moved from exploring biomorphic forms and abstracted concepts to a focused examination of New Zealand’s Māori and Pākehā cultural histories, often referencing painted meeting houses created under the Māori prophet Te Kooti Arikirangi Te Tūruki.

His art practice has been the subject of significant exhibition and publications and his paintings have led exhibition projects extensively here in Aotearoa but also throughout Australia, The United States and across Europe. Key exhibitions include: Kohia Ko Taikaka Anake, National Art Gallery, Wellington (1991); Shane Cotton Survey 1993–2003, City Gallery Wellington Te Whare Toi (2003) and Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki (2004); Paradise Now? Contemporary Art from the Pacific, Asia Society Museum, New York (2004); The Hanging Sky, Institute of Modern Art, Brisbane, touring to City Gallery Wellington, Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū and Campbelltown Arts Centre, Sydney (2012–13). His work was also featured in Toi Tu Toi Ora: Contemporary Māori Art, Auckland Art Gallery in 2020. In 1988, Cotton was the Frances Hodgkins Fellow at the University of Otago, Dunedin and received the Seppelt Contemporary Art Award from Sydney Museum of Contemporary Art that same year. In 1999, he was awarded a Te Tohu Mahi Hou a Te Waka Toi/Te Waka Toi Award for New Work; and he became an Arts Foundation of New Zealand Laureate in 2008. Cotton represented New Zealand at the 2005 Prague Biennale and his work was included in the 17th Biennale of Sydney 2010. He was appointed an Officer of the New Zealand Order of Merit, for services to the visual arts, in the 2012. Shane Cotton lives and works in Russell, Northland.

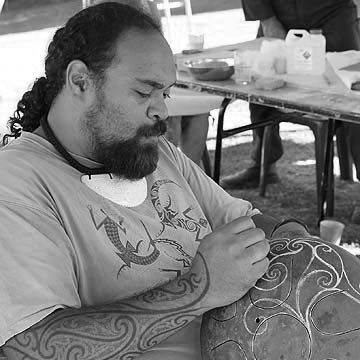

Amorangi Hikuroa works to honour the whakapapa of Māori uku practices through Te Moana-nui-a-Kiwa and beyond. Collecting, forming, softening, working, pausing, returning; uku belongs to an ecology of processes.

Fostered by those who form the pillars of Ngā Kaihanga Uku, the works shaped by Hikuroa demonstrate that the practice of uku is not one of solo pursuit, but of a collective journey – (re)entering the slipstream of tūpuna consciousness. Hikuroa embodies the complex, enduring and living legacies of ancestral knowledge within his works.

“We have avenues where uku can now be utilised within our culture, as ritual ware to mahi kai. Made relevant by our mentors and founders of Ngā Kaihanga Uku. So I pay homage to them for giving Māori a pathway back to our ancestral links within the Pacific and reconnecting Māori back to the most ancient of human art forms.”

Aroha Gossage lives and works on her papakāinga in Pākiri. Gossage’s continued occupation, along with her whānau, on their whenua keep the home fires burning – ahi kā. The connection the artist has to her whenua is noted in both the content and material of her paintings. Gossage depicts the land in her imagery, using kōkōwai collected from the rohe. The earth pigment is mixed with oil paints, providing an atmospheric character to her work. As Gossage herself tells, the inherent force of the land exists in the earth pigments she uses, which is also the same force that exists within her.

“I know where to go to get rich reds, up by the dam. There are pure whites and blues if you dig a metre down in a special spot under our bridge. The ochres are on the corner by the gravel road up by my Aunties’ and I find lovely greys at our waterfall. These rich earth colours you can't buy in a tube.”

“In my language journey you are introduced to stories from all over the country. You’re also introduced to different accounts of the same story. One thing that I’ve been fortunate enough to experience, from hearing different people’s perspectives, is that there isn’t necessarily a disregarding of other accounts, even though they might contradict one’s own account. It’s just accepted that that story exists, and this story exists.”

Raukura Turei explores ngā mareikura and tupuna wāhine alongside notions of longing and return. Turei’s practice itself is a vehicle for return. Both in the acts of collecting onepū from Paruroa and aumoana from Maraetai, and the meditation of her mark-making – which in its repetition, calls and echoes Turei’s own return and re-connection with her whenua and whakapapa.

Star Gossage pulls memory, land, longing, and occupation into her paintings. Often the artist portrays wāhine, appearing almost as apparitions that might fade the next time you look. These indistinguishable women allow you to see a crowd of people within them, perhaps self-portrait, perhaps a sister, a memory, tupuna, mother, grandmother.

Like her sister Aroha, Star works with kokowai in her images. Again, the connection to whenua is intrinsic, imbued into the artwork – as if not for one second should we, the land and I, be apart. Perhaps the melancholy of Gossage’s work is the recognition that some land we have been forcibly parted from, the weight of wanting to reconnect shared by many Māori. However, like the people she paints you can see different moods in the same work. Where at once you might encounter the work’s melancholy, upon the next glance you will experience peacefulness.

“The whakapapa is connected here, in this land because our ancestors have always lived here, since the beginning. They’ve always been here and they’ve always connected here, that’s why we’re still here. They’re in the land and we’re here with them. It’s a long time that my family have been here. My grandmother said “from the beginning of time we’ve been here.” So that’s what we always used to say - yeah, yeah we’re still here.”

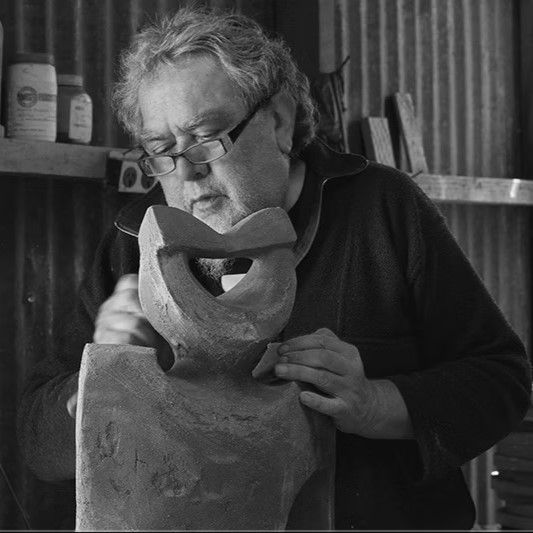

Tracy Keiths’ clay sculptures are part dedicated research and part intuition, where the agency of artist and material both influence the outcome. Once the finished form is revealed Keith proceeds with a two-fire process. Firstly, a bisque-fired technique that is then followed by a 500-year old Japanese technique called Raku. Keith acknowledges the whakapapa of the material, as well as his process in his artwork.

The sculptures have an industrial appearance or perhaps it is the look of the land where we have cut into it for mines or quarries. Despite their titles, works like The Skin of Papatūānuku clash with our expectations of a landscape. Keith is showing us a more realistic portrait of the land, using the land – which is the place we come from and will one day return.

“Shards of earth splintering the flesh of the land protruding and piercing the surfaces creating divisions that disrupted the natural order of the container, they are non-utilitarian in a sense they have become unusable and contain the memory of a vessel.”

Ngāpuhi, Ngāi Tūpoto, Ngāti Hine, Ngāituteauru

Lisa Reihana, CNZM is a pioneering moving image and digital media artist. Of Ngapuhi descent Reihana’s practice spans across four decades as she innovatively explores history, culture, and identity through performance, photography, installations, and multimedia. Her immersive works traverse fact and fiction, offering an interpretive viewpoint that beings fresh perspectives on colonial encounters and the dynamics between indigenous communities and European settlers.

Through her groundbreaking artistic contributions, Lisa Reihana has played a key role in the development of video, film and moving image within contemporary New Zealand art and her practice has made a significant contribution to the development of Māori moving image and contemporary Māori art inspiring a new generation of Māori digital media artists.

Ko Lisa Reihana MNZM he whakaatūranga nukunuku paionia me te ringa toi matihiko pae pāpāho Nō te taihekenga Ngāpuhi ko ngā mahi a Reihana ka whakawhitiwhiti i te whā tekau tau me tana totoro auaha i te hitōria, te ahurea, me te tuakiri mā roto i te whakaataata, te tango whakaahua, ngā puninga me ngā rongo rau. Ko ana mahi ruruku ka whakawhiti i te meka me te kōrero paki, ka tohatoha i te tirohanga whakamāori ka kawe tirohanga hou ki runga i ngā whakataunga whakataiwhenua me ngā hihiritanga waenganui i ngā hāpori taketake me ngā tāngata whai Pākehā.

(Ngāpuhi, Te Roroa, Ngāti Whātua)

b. 1947

Alex Nathan is a leading Māori silversmith, jeweller, and cultural advocate whose work spans over 30 years. Nathan is revered for his masterful use of traditional Māori designs in materials such as sterling silver, copper, bone, and shell.

Alex has played a pivotal role in nurturing Māori art in the Far North, helping young artists develop their skills through workshops and programmes. He continues to pass down his knowledge to emerging artists and inspire a new generation of Māori jewellers and makers.

Nathan's journey into silversmithing began in 1991 when he was introduced to the Hopi overlay method. His work blends traditional Māori motifs drawn from whakairo (carving), kōwhaiwhai (scroll patterns), tukutuku (latticework), and tāniko (woven patterns), creating unique, hand-carved adornments that are works of art in their own right.

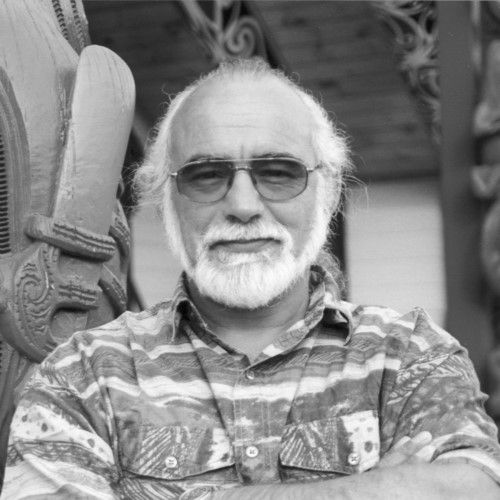

(Ngāpuhi)

b. 1955

Allen Wihongi MNZM is a distinguished Māori artist and leader, celebrated for his contributions to both the arts and his iwi, Ngāpuhi. His career spans over 30 years, during which he has become a key figure in both the education and art sectors of Aotearoa.

Wihongi is highly regarded for his work in whakairo (carving) and mixed-media art. His creations are characterised by a deep connection to his Ngāpuhi heritage and a commitment to preserving and advancing Māori art forms. This is evident in his ability to incorporate Māori design principles into large-scale national projects, most notably as the Māori design consultant for the Tomb of the Unknown Warrior at the National War Memorial in Wellington. These projects showcase his ability to convey powerful narratives of cultural identity and memory through visual art.

Allen Wihongi - Te Waka Toi Awards 2019 interview

(Ngāti Porou, Te Whānau-a-Ruataupare)

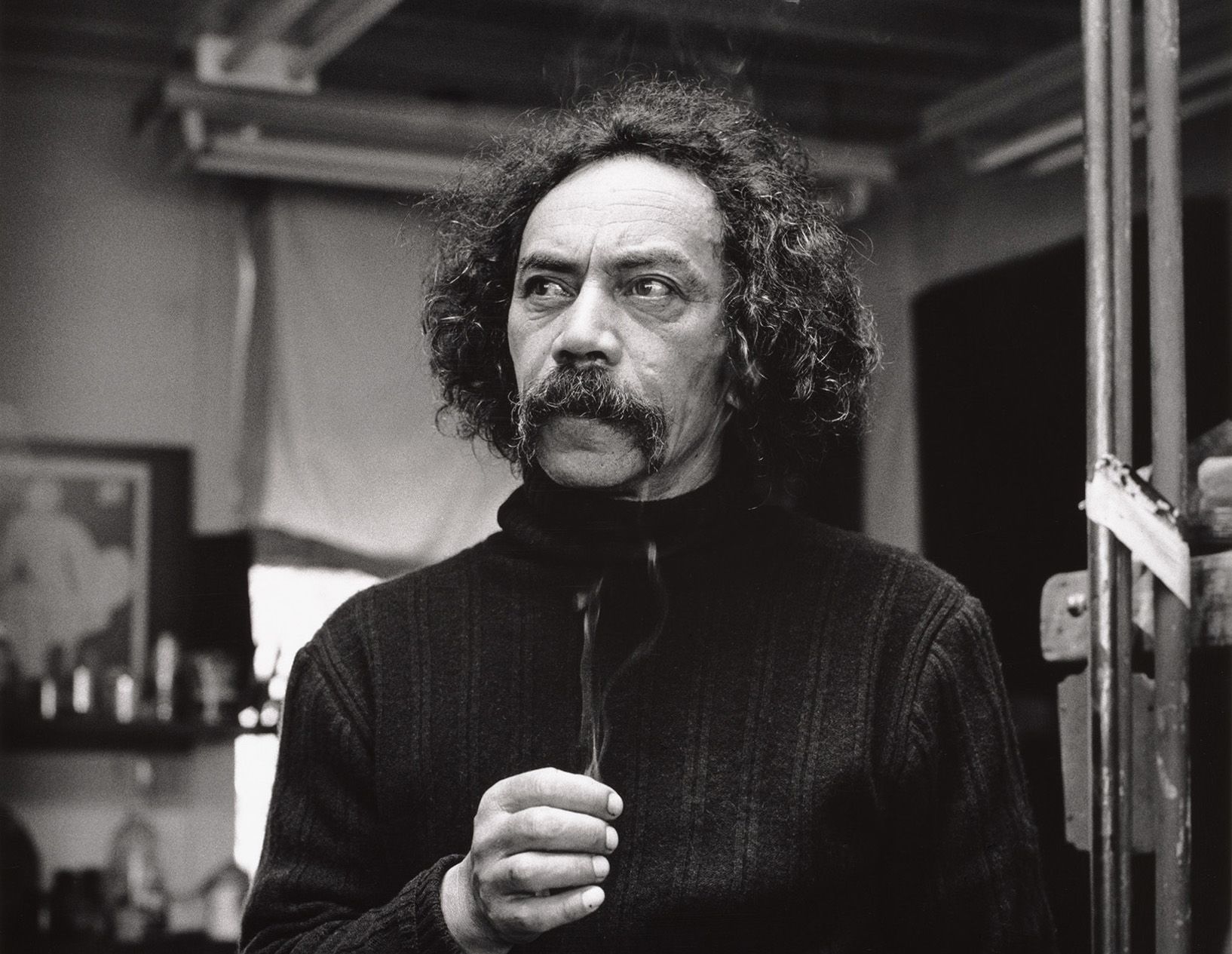

b. 1950

Baye Riddell is a pioneering New Zealand ceramicist and clay worker.

Riddell's connection with clay began in Christchurch in the early 1970s, during a period when he had become distanced from his Māori identity. As he began incorporating Māori design elements into his pottery, Riddell embarked on a journey of reconnection with his whakapapa.

Riddell became deeply involved in the resurgent contemporary Māori art movement, founding Ngā Kaihanga Uku in 1986, a national Māori clayworkers' organisation that would become a cornerstone for Māori ceramic artists.

Riddell's legacy is not only his work in ceramics but also his role in shaping the Māori voice within contemporary New Zealand art.

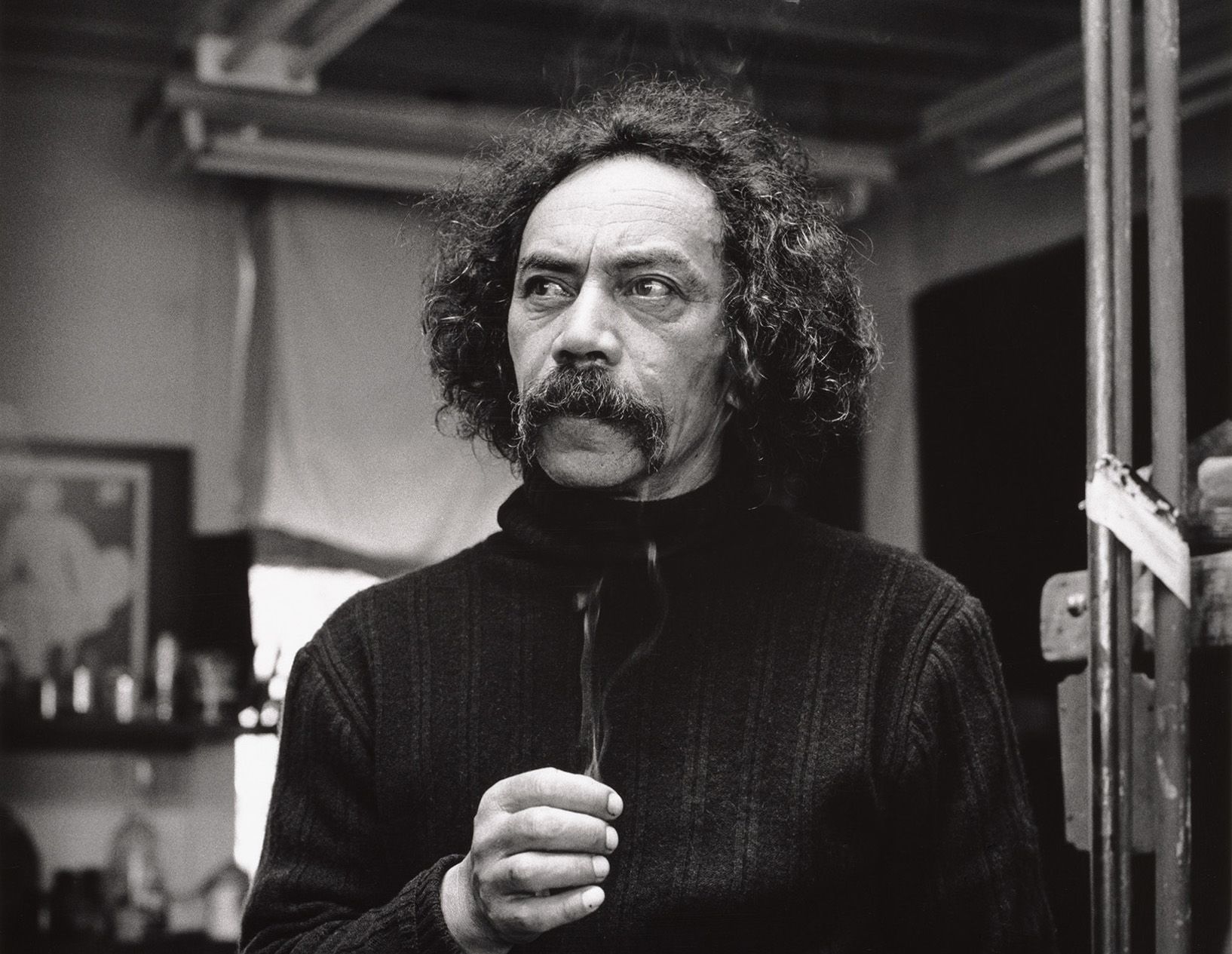

(Ngāi Tūhoe)

b. 1947

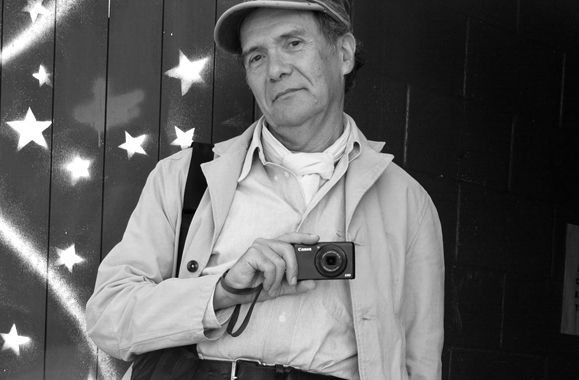

Donn Ratana is a sculptor and painter recognised for his multifaceted artistic practice and contributions to arts education. He hails from Murupara, a rural Māori settlement, where his upbringing fostered a deep connection to creativity and resourcefulness. His artistic journey spans over 50 years, encompassing drawing, sculpture, assemblage, and painting. Ratana is often described as one of Aotearoa's unsung art heroes, celebrated for his ability to engage with cultural issues like colonisation and Māori self-determination through humour and wit.

In addition to his artistic endeavours, Ratana has made significant contributions as an arts educator, particularly at the University of Waikato. His work often reflects the themes of innovation and inquiry, and he emphasises the importance of creativity in education.

Interview with Donn Ratana

(Ngāpuhi, Te Atiawa)

b. 1947

Gabrielle Belz has been a force in Aotearoa's art scene for decades, both as a painter and a printmaker. Her work speaks to the soul of the land, its natural history, and the people who shape it. Belz's work is a visual symphony of indigenous identity.

Belz's career is devoted to ensuring the growth and sustainability of Māori art, often advocating for spaces where creativity and culture flourish side by side.

Interview with Gabriel Belz | Te Waka Toi Awards 2022

(Ngāti Maniapoto, Waikato, Te Arawa, and Scottish (Katimana)

b. 1969

James Ormsby is a distinguished artist known for his meticulous work in drawing, which he describes as his "first language". His art is deeply rooted in his bicultural heritage, and he integrates both Māori and Scottish influences, reflecting on the visual symbols and materials his ancestors would have used. Ormsby's work often explores themes of history and spirituality.

Ormsby's works are characterised by precise, complex studies of cultural and mathematical systems, informed by his research into ancient sketches and documents. His style combines restrained brush and pencil marks with an atmospheric approach to colour, often working in materials like graphite, oils, and inks.

Ormsby is, by nature, curious about the shared visual language and material that exists between our past and present. From his experience, when our material culture is practised, it is like exercising a kind of tissue between past and present, which in turn maintains a body of mythic inheritance or understandings. Ormsby's artworks have attempted to link old marks with new audiences and here whakapapa (genealogy) with whakapono (spirituality).

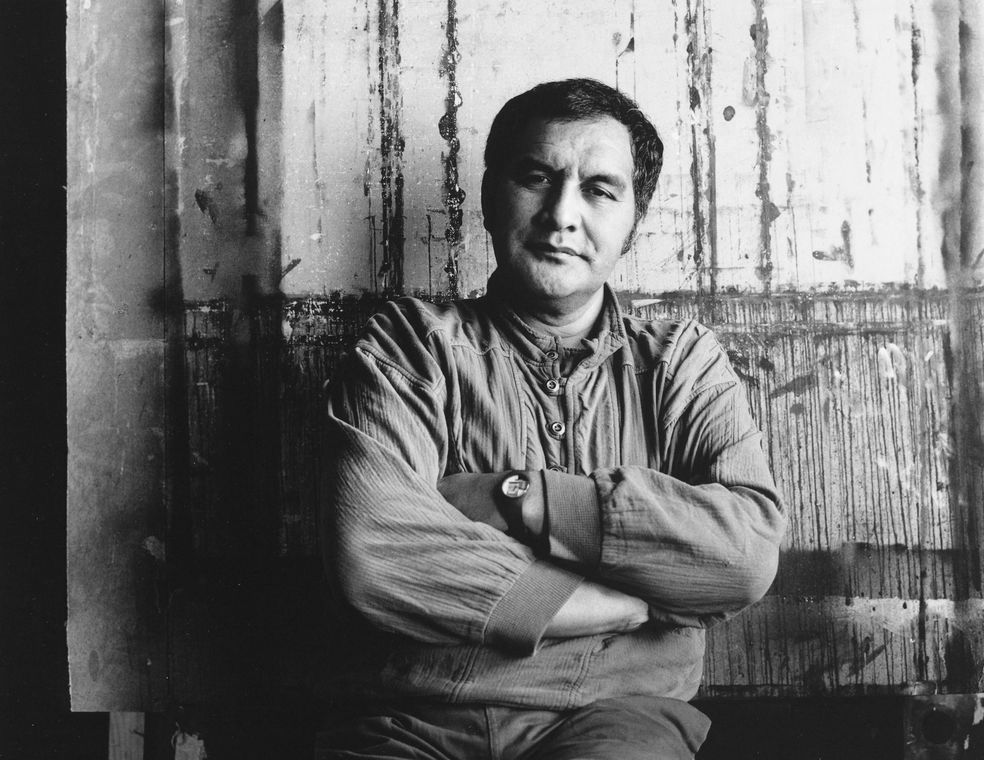

(Ngāti Tūhourangi, Ngāti Wahiao, Ngāti Tūwharetoa)

b. 1949

June Grant ONZM is a celebrated Māori artist whose work is inspired by her whakapapa. Grant's art is packed with symbolism that tells narratives about tūpuna, such as the famous Whakarewarewa guide, Makereti Papakura. Her art speaks to histories in Aotearoa through a modern lens.

Grant's commitment to Māori is a widely cast net. She has been a tireless advocate for Māori artists, supporting the development of Māori art in schools and playing a key role in initiatives that uplift emerging Māori women artists.

(Ngāti Kahungunu, Ngāti Pāhauwera)

b. 1939

Sandy Adsett (MNZM) is one of Aotearoa's most iconic contemporary Māori artists and is considered a master of kōwhaiwhai and colour.

Beyond his own practice, Adsett has had a profound impact on Māori visual arts education, where he has mentored generations of Māori artists. His students, many of whom have become prominent figures in New Zealand's art world, carry forward his legacy of integrating Māori identity and tradition into contemporary art.

(Ngāti Pikiao, Te Arawa, Te Āti Awa, Ngāti Te Roro o Te Rangi, Ngāti Whakaue)

b. 1946

Wi Taepa ONZM is a pioneering figure in Māori ceramics.

Initially trained in wood carving, Taepa transitioned to clay in the mid-1980s. His early experimentation led him to embrace hand-building techniques, such as coiling, pinching, and slab-building, rejecting the traditional potter's wheel. His work draws on kōwhaiwhai, tukutuku, and carving-inspired punch markings, expressing his indigenous voice through fresh new forms and techniques.

Taepa was instrumental in founding Ngā Kaihanga Uku, a collective of Māori clay artists that included notable figures such as Manos Nathan, Baye Riddell, Paerau Corneal, and Colleen Waata Urlich. Through Ngā Kaihanga Uku, Taepa helped elevate Māori ceramics into national and international art discourse.

Taepa has mentored new generations of Māori artists, inspiring through both his work and his teachings.

(Ngāti Tūwharetoa, Te Rarawa, Fijian)

b. 1978

Margaret Aull is a prominent curator, artist, and arts manager known for her interdisciplinary approach and advocacy within the arts sector. She has a rich history of curating exhibitions that engage deeply with cultural narratives and wellbeing, most notably co-curating the 2022 exhibition 'Toi is Rongoā' at Waikato Museum, which explored the relationship between art and healing. Her leadership reflects her commitment to using art as a tool for community engagement and cultural rejuvenation.

In addition to her curatorial work, Aull's own artistic practice spans installation, painting, and sculpture, often exploring the intersections of her Māori and Fijian heritage. She has exhibited widely in both solo and group exhibitions across Aotearoa, the Pacific, and beyond, with her work delving into themes of whakapapa, ritual, and belief systems. Her role as the current Chair of the Te Ātinga Contemporary Māori Arts Committee and her past positions as Tumu Herenga Toi at the New Zealand Māori Arts and Crafts Institute and Collection Curator at Te Wānanga o Aotearoa further highlight her influence in shaping and supporting the contemporary Māori art scene.